Winery Diego Mathier

Valais wine quality for generations

Discover our award-winning wines and find out more about the Diego Mathier family winery.

Cuvée Madame white

Rosmarie Mathier

AOC Valais

Cuvée Madame red

Rosmarie Mathier

AOC Valais

The infernal

Pinot Noir Lucifer

AOC Valais

The nose

Syrah Diego Mathier

AOC Valais

Love

Merlot Nadia Mathier

AOC Valais

Excellent

Award-winning Valais wines from Grand Cru vineyards

You can conveniently order our award-winning wines to your home.

Mathier Salgesch

Ambassadors of incomparable moments of pleasure in a glass

As an award-winning, 4th generation family business with over 60 Valais AOC wines from Grand Cru vineyards, we see ourselves as ambassadors of incomparable moments of pleasure in a glass. Our wine philosophy, in which tradition and innovation successfully go hand in hand, is also an expression of our commitment to sustainability and a deep connection to the region.

Sustainability

All our actions are based on a considerate use of resources to preserve sustainable Valais wines for future generations.

Innovation

Constantly questioning ourselves and the careful combination of traditional and modern elements guarantee our continuous development.

Philosophy of the Mathier family

Our values

Emotion

Share joy & passion for Valais wines with friends of the Mathier family. Experience emotion & pleasure.

Quality

Striving for the highest wine quality and continuity through constant questioning.

Tradition

The Mathier family's tradition is to pass on the flame for maximum enjoyment & preservation of knowledge.

Sustainability

Careful use of all resources to preserve sustainable Valais wines for future generations.

Innovation

State-of-the-art technology paired with knowledge, experience and creativity are the breeding ground for innovation in the Diego Mathier family.

Generation

Perfection is the driving force behind the Mathier family's refinement of wines in the fourth generation. Wines of the highest quality are a matter of honor.

Emotion

Share joy & passion for Valais wines with friends of the Mathier family. Experience emotion & pleasure.

Quality

Striving for the highest wine quality and continuity through constant questioning.

Tradition

The Mathier family’s tradition is to pass on the flame for maximum enjoyment & preservation of knowledge.

Sustainability

Careful use of all resources to preserve sustainable Valais wines for future generations.

Innovation

State-of-the-art technology paired with knowledge, experience and creativity are the breeding ground for innovation in the Diego Mathier family.

Generation

Perfection is the driving force behind the Mathier family’s refinement of wines in the fourth generation. Wines of the highest quality are a matter of honor.

Seasonal wine recommendation

Wines for the game season

Free home delivery from 12 bottles with attractive quantity discounts

Wine experiences

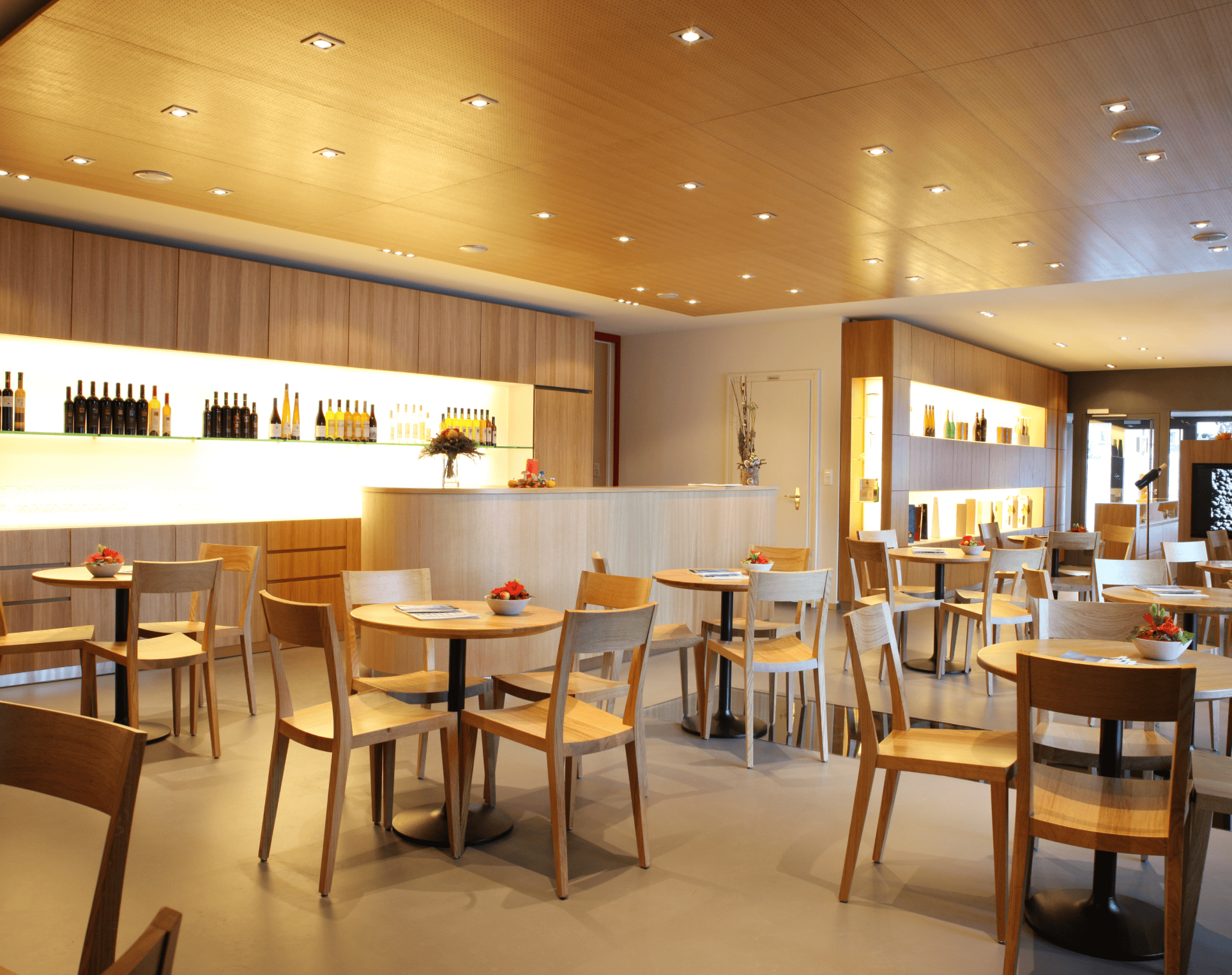

Tasting Valais wines

Taste our award-winning Valais AOC wines in Salgesch, Interlaken, Hochdorf or at one of the numerous public fairs in Switzerland. Unique wine events and enjoyable wine vacations at the BnB Vino Veritas complete our incomparable wine experience offer – perfect for wine lovers and connoisseurs of special moments.

Tasting

Wine tastings with guided wine walks through the vineyards - individually or in groups.

Wine vacation

Unforgettable wine vacations all year round at the BnB Vino Veritas in Salgesch in modern De Luxe studios and suites.

What makes Mathier wines special

Switzerland's most successful winery

Over 1,000 national and international awards at prestigious wine competitions worldwide.

Best Grand Cru vineyards in Valais

Over 45 hectares of outstanding cru sites from Turtmann to Chamoson are owned by the Mathier family.

Wide range of Valais AOC wines

Over 60 different white wines, rosé wines, red wines, dessert wines and sparkling wines.

Gift ideas

Wines to give as gifts

Discover our gift ideas in wooden boxes of 2, 3 and 6 as well as large bottles

Reviews

Customer testimonials

Find out what our customers have to say about their wine experiences with us.

Rate us

The team at Adrian & Diego Mathier Nouveau Salquenen is delighted with every good review of Mathier wines.

"Excellent wines and served by qualified staff who are very familiar with the history, the grape varieties and the different wine ranges."

"Very good wines with the right price/performance ratio. The contact with the Mathier family and their employees is always very friendly and well-positioned.

"Super nice wine shop and very cozy ambience. Great family business. We really enjoyed it, the wines are great. Highly recommended for all travelers to Valais."

"Top wines! Large selection! Extremely friendly hosts! I felt very comfortable during my visit to Salgesch. I can warmly recommend it."

#mathier

Mathier's world of wine

News from the world of Valais wines from the Diego Mathier family

News

Diego Mathier joins the select club of winemaking legends in the wine magazine Vinum.

Trade fairs & events

Visit us at one of the numerous spring fairs in 2025 or at one of our wine events.

Wine tastings

Taste our award-winning wines in Salgesch, Hochdorf (LU) or Interlaken (BE).

Wine vacation

Wine vacations in the heart of Valais at the BnB Vino Veritas in the wine village of Salgesch.

Wine magazine

Discover exciting video messages and articles about the world of Valais wines.

Trade fairs & events

Visit us at one of our spring or fall fairs or at one of our wine events.

Subscribe to our newsletter & benefit

Subscribe to our newsletter and benefit from interesting offers.

By clicking on Register you confirm that you accept our TERMS AND CONDITIONS accept.

Do you have any questions?

If you have any questions or inquiries, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Send us an e-mail and we will get back to you as soon as possible.

Telephone

Give us a call and speak directly to one of our employees.

Social Media

Contact us on our social media channels.